- Tangential

- Posts

- 💿 We Don't Listen to Albums Anymore

💿 We Don't Listen to Albums Anymore

How creating and consuming content has changed for good, and is about to get weirder

Music has long been dominated by the album format. Albums have, for a large part of the history of recorded music, been the default way of grouping songs together. To our generation though, listening to albums feels nostalgic, not typical. Think about the last time you actually heard an album chronologically instead of your favorite playlist on shuffle. Think about your current top 5 songs and try to name which album each of them is from. If your memory fails you on either of these questions, don’t mind your mind, it’s just a sign of the times.

When you play music on your iPhone today, the lock screen shows you only the song’s name and artist, not the album. It’s the kind of trivial change that most don’t even notice. To be honest even as someone who clocks hours on the Spotify every week, it took me a while to notice. But when I did notice this, it got me thinking about how we consume music, and why that has changed over the years.

Distribution is King

A great way to start figuring out the cause of the collapse of the album is by looking at how music is distributed now, and what has changed about it in the past decades. The way money is made, the way money was made. The device you listen to your music on, the devices you used to listen to your music on. The ways you find new music, and how you did in the past. Broadly, the economics of it all.

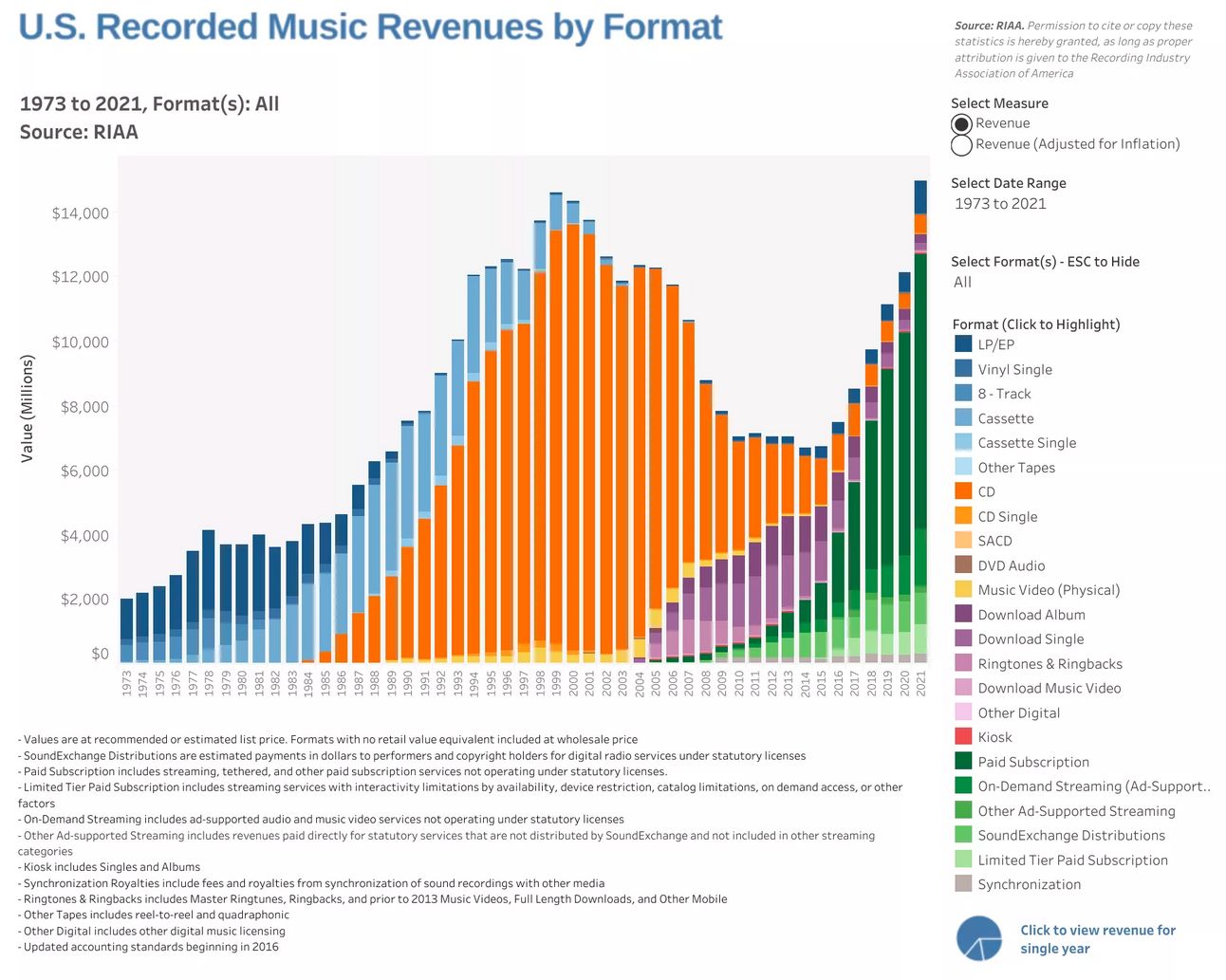

Until the mid-2000s, album formats — EP/LPs, Vinyl, Cassettes and CDs — made up functionally all of the recorded music revenue in the US. Today these once great formats have been reduced to being meager footnotes. Not irrelevant, but certainly not significant. So why did people suddenly stop buying albums?

The simple answer is way simpler than you would expect — people stopped buying albums because they finally could.

Before the internet became the main source of distribution for music, the physical formats came with inherent limitations you could not negotiate with. To sell any music, let’s say on a CD, you would have to bear certain costs that don’t change much based on how many songs you have on a CD. One song? Ten songs? Doesn’t matter — as an artist/label you still have to purchase the physical CD, the cover, get both of those designed and printed, and finally delivered to a CD store. Whatever you have on that CD, you have to sell it for around $10 or more if you don’t intend to lose money on the deal.

This made the default format of distribution, and thus consumption, full albums. Only a fool would buy a CD with a single or 3 songs for the same price they would buy a 10 song album. More is always better. So, for the longest time, these constraints defined the music industry, and the album became a storytelling format for artists. Even if the album was not one cohesive narrative, good albums usually made deeper sense when heard in the intended order. Good albums are greater than the sum of their parts.

When the internet introduced a new way of getting your music to people, things got pretty weird pretty quickly. Artists or labels could, for the first time, profitably sell one song for much cheaper than they would sell a whole album. The rational way changed from being “more is always better” to “only buy what you need.”

When music streaming became the default, the barriers became even lower and the demise of the album hastened. Typically, aspiring artists would have to put together 10+ release quality songs to ever stand a chance to get a label to release their music — most artists could not afford the up front costs of printing a batch of CDs, getting them shipped to stores and paying stores to display them prominently. With streaming, you didn’t need a label — there is a negligible cost to getting your music on Spotify. If you had 3 good songs, you didn’t need 7 more to stand a chance.

Streaming fundamentally changed how artists share their music and how we consume. Artists like Billie Eilish, Ritviz and Lil Nas X had millions of streams on their songs and were bonafide celebrities before ever releasing an album. Something like this would be hard to imagine even 20 years ago, but music has changed for good now.

Artists can finally stop making albums and we can finally stop buying them.

So we’ve figured out so far that the internet has caused a massive shift in the economics of how music reaches us, and that in turn affects how we consume it. In fact, the example of albums and music is very much representative of media in general — think being able to read blogs instead of books, or watching YouTube videos or Reels instead of movies. But the effects of technology on media are not limited to just the distribution side of things, if anything the creation side has been affected even more, and will cause an even greater shift in the near future.

The Infinite Content Machine

Its not just distribution that has changed how we consume content, the creation side of things is incredibly important to consider too. With advances in technology over time, especially with computers and the internet, creating media has also become much simpler over time.

To illustrate, imagine you were an aspiring video director around the year 1960. What would it take for you to be able to delete the unfortunate prefix of “aspiring” from your title and graduate to being a filmmaker? A camera, of course. Well the first video camera, launched in 1956, costed at least $45,000 which is a cool $450,000 when adjusted for inflation.

But maybe you have that kind of money lying around, what else would you need? A cast, a crew, a videographer and more. Making videos in any sort of commercially viable way just 60 years ago was impossible.

Now each one of the nearly 7 Billion smartphone owners in the world can do what took months of effort and incredible amounts of investment. Think of the many video based content creators who are making a living with just their phone. Even entire indie movies which have grossed millions of dollars in the box office have been made using just phones.

This is a massive paradigm shift in creation. What applies to video applies equally to image and music creation. This is why we live in an age where we are constantly flooded with new content. The post-renaissance era commoner didn’t have the luxury of getting bored after a day of listening to the latest Mozart banger. Compare that to now where 5.4 billion people with internet access for whom an average of 2,500 new videos are uploaded to YouTube every minute, amounting to 183 hours of video content.

The ease of creation is about to get much easier still with recent advancements in AI. Midjourney for image creation, emerging platforms like Suno for music, OpenAI’s Sora for video and any companion for text means that anyone can produce prolific amounts of content with ease.

Can you believe this song is entirely AI generated (including the lyrics, voice and instrumentals):

Leonardo took around 3-4 years to paint the last supper. I used midjourney to create the last pupper in 5 minutes. Of course there is no comparing the quality (the last pupper is probably a generational work of art), but I think this illustrates really well the unbelievable difference in efforts required to create original images.

The Last Supper |  The Last Pupper |

The Exit Option

Now that there is so much music to listen to, so many TV shows to watch, so many reels to scroll, so many video games to play and so many blogs to read, its become harder to choose what to spend your time on. At the end of the day, you only have so much time to spend on all of these combined.

This often leads to a certain kind of decision paralysis where the sheer number of options make it hard to do anything. I’m sure I’m not the only one who has spent 20 minutes just browsing Netflix before either giving up or rewatching a sitcom. Economists call this the paradox of choice — theoretically having more options is better, but beyond a certain point the increased cognitive load in making a choice outweighs the benefits of having more choices.

The number of choices we have might be part of the reason why short-form content is taking over. When you’re opening up Reels or Twitter, you are not committing to any specific amount of time to spend on it. There is no major FOMO about everything else you could be watching because you can stop this midway at any time. How often you end up scrolling for less than 10 minutes is a different question entirely, but in your mind at least you are maintaining your “exit option.”

I think short form content is affecting our attention spans, but the exit option is probably a more useful lens to look at it. People still do consume a lot of long-form content, for eg. watching TV shows that span 10+ seasons and listening to 2 hour long podcasts. What these examples have in common is the exit option though, you may not feel as much FOMO because you can stop at any point to switch to something else. You can quit a TV show after the first episode and you’ve only lost 30 minutes of time that could have been spent consuming other content. You can stop a podcast midway and come back to it weeks later if you choose to, since most of them are not a single narrative but more conversational.

The perceived opportunity cost of choosing to watch/read any specific thing over others is probably the most important part of why our viewing habits are so different from previous generations.

Techincally Speaking

So we know now that seismic changes in creation and distribution have strongly affected how we consume, but what about creators? The handbook for them has changed even more with time, and what seems to matter most now is something as simple seeming as good taste.

I was around 7 years old when Abra Ka Dabra, the first Indian movie in 3D came to theatres. For the longest time, probably because I never rewatched it after my brain fully developed, I remembered it being an incredible movie and experience. Its not a good movie by any stretch of the imagination. I know that now, but back when 3D movies were new and difficult, it felt like the pinnacle of cinema to me.

I think there are two phases of change in terms of what is needed to succeed with a certain format of media. The first shift is from it being novel → being possible. Then from being possible → being easy. In the novelty phase, the fact that not many people have the resources to do it as well as the technical difficulty involved makes all other aspects almost secondary. Remember that beer app that was all the craze when the iPhone just came out, how well would it do now?

When things go from being novel to being possible, there is still a level of technical ability that is required to be successful, but good taste becomes important as well. Now that feature length films are very much possible to make, you need more than just good camera work to impress audiences. Good script, dialogue, acting, background score, pacing, etc. all determine whether a film does well.

The final change from possible to easy is the most significant one, and a phase we are hitting now. Already, all you need to make YouTube videos is a smartphone. The technical floor is lifted so much for all creators that the difference in camera quality and work becomes hard to notice outside that of the handful of top-tier creators. What remains is how you resonate with your audience, an admittedly vague north star.

As AI generated video, music and text make the easy trivial, it will make things simultaneously easier and much harder for content creators. Easier in the sense of actually creating content, anyone can do that in minutes now. Much much much harder in terms of being successful as a content creator — when you are competing with 5 billion people, it becomes that much harder to stand out. You need great taste to make a mark.

The ease of creating content has also given rise to a whole new class of creators — curators as creators. These people fully embody the fact that good taste is the only prerequisite to making it as a creator now. Think of the people you look to for book recommendations, they are not writing those books themselves. Think about those YouTubers who always seem to find the funniest videos so you can watch their reaction to it rather than needing to find good videos on your own. Or pop culture influencers who have contributed to you discovering about half of your playlist.

This is a new era of creation entirely. The visualizations below might help think about what it takes to succeed during the Novelty Era of something compared to what it takes to succeed in the Easy Era.

This is exciting because it has empowered so many more people to succeed at something they could not have dreamed of a few years ago. The aspiring video director we talked a few sections ago now has the ability, regardless of (for the most part) where they are in the world or their economic situation. There’s something undeniably beautiful about that.

Reply